A lot of mysticism and spirituality focuses on the question of who “you” truly are. How there’s “a true self” or “no self”, and how you can come to realize that truth through meditation or whatever.

But I think the discussion tends to cloak why we should care.

For instance, many Buddhisms talk about freedom from suffering, and how suffering arises due to a confusion in your sense of self. And sure, there are probably ways I make my life more miserable than it needs to be as a result of how I view it and/or myself. But if I’m lonely, or hungry, or in physical pain, why would I want to solve that by messing with my psychology? Why not get satisfaction by solving the underlying problem?

Calling that attitude “more confusion” really doesn’t clarify anything. It makes Buddhism sound confused! Why would I want a solution to my problems that sounds indistinguishable from ceasing to care about my life?

Ironically, I think the discussion sounds like this because most people are confused about the nature of the self. But I don’t think that has to be a source of endless paradox. It seems to me that the situation can be clearly stated and mentally understood with some effort. At which point the “why” behind a lot of spiritual practices becomes a lot more obvious. And I think that’s a good thing.

So in this post I want to spell out a possible explanation for “the self” that I find both clarifying and pragmatic.

By that very model, though, it’ll work better if I start with an example of why it matters. What kind of problem this understanding can solve. So let me start there. Just be aware that I don’t mean this to be a description of all problems that can arise from identity confusion! I’m simply trying to point out a reason why you might want to care.

Sticky problems

Some problems fight being solved. They’re not merely hard to solve; they strategically shapeshift so as to prevent solutions from working.

One example is “anxious attachment” (i.e. being clingy in relationships). There’s a certain kind of person who tends to get very needy and insecure when dating someone. That neediness can then drive the person they’re dating to put up emotional walls. When such a person learns about attachment theory, they’ll often get excited because they see a tool for resolving relationship problems and getting closer. So they’ll try to pressure their now-resistant partner to put even more effort into the relationship. Thus an understanding of why their connection is glitchy gets used to make their connection more glitchy. The clinginess prevents its own solution.

There are tons of examples like this. My breakdown of the Enneagram points at nine such clusters. For instance, one personality design (“type One”) wants to make sure their own behavior and ways of thinking are perfectly good and right. When they learn about this pattern from the Enneagram, they have some tendency to try to purge themselves of their perfectionism, implicitly seeing it as wrong or sinful. That’s of course an effort made of irony. If they notice that irony, their tendency is to get rigid and harsh with themselves and to try even harder. Their perfectionism prevents itself from being softened.

It’s not a coincidence that so many of these error modes go through the sense of self. “I’m too needy” or “I’m too hard on myself” or whatever. Needing a job is just a pragmatic issue, but it becomes a self-reinforcing problem when it becomes part of identity: “I’m such a loser, no one wants to hire me, I’m worthless.” At which point it becomes a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy!

To be clear, I’m not saying that all such sticky problems go through the sense of self. I’m saying that some do, and that de-confusing the sense of self can resolve many of them.

At this point, if I were teaching this as a live class, I’d invite those attending to spend a minute or so jotting down some stubborn problems in their own lives. Ones they’ve tried to solve but that seem to stick around no matter what they do. Chances are that at least one of those problems will start to look more solvable as a result of what I’m about to lay out. But it really does matter to have them in mind before going over the general theory.

So: I encourage you to pause and think of a few such challenges in your own life. I know that breaks reading flow a bit, and if you prefer a fluid reading experience then by all means carry on. But I really do mean less than a minute of reflecting. I’ll explain later on why that’s important.

How I think self works

Here’s my explanation for identity in short:

Minds solve problems. That’s all they do.

Minds construct a sense of self to track which tools they can use to solve problems.

Minds also construct our sense of objects to help with problem solving.

In particular, to solve certain social problems, minds tend to create a vision of ourselves as seen from the outside, and then to treat those visions as real objects.

This setup is great for solving some problems, but it’s systematically bad at solving some others. If we’re clear about precisely what that distinction is, then the mind can change how we’re using identity such that some of those sticky problems become a lot easier to approach.

Let’s dive into some detail here.

Minds solve problems

When I say “mind”, I’m trying to point at a kind of module that shows up in subjective experience. It’s where thoughts come from, and what produces speech. (How do you take a feeling and articulate it? What’s that subjective experience like?) It’s also what you consult when you’re trying to remember someone’s name. (If you try and try and try, and then set the effort aside, and then a minute later the answer blasts into your awareness… where does the answer come from?)

I sometimes find it helpful to imagine the mind as some kind of internal computer that I’m using. I give it a prompt, and it runs off and does some computation in the background, and then it gives a response. Sometimes it responds instantly, but sometimes it takes a while. (Hence the forgotten name “coming to mind” a little while later.) Or maybe a bit like I have a secretary or genie who lives in the back of my head, and I make requests of them.

(For now, don’t worry too much about who “I” am in this picture.)

I claim that all the mind ever does is try to solve problems. All mental activity is part of some strategy for achieving some goal. Every thought — even a “random” one — arises for a reason. It’s always targeted.

In particular, you can always in principle connect a thought back to a prompt — often one you gave at some point.

Sometimes this connection is very obvious. If the conversation has moved on from remembering the guy’s name to politics or whatever, and you suddenly think “His name is John Glover!”, you’re not confused about why you’re thinking of that name. The thought sort of comes tagged with what prompt it’s attached to.

At other times it’s much more subtle. You might start thinking about how you need to reply to that one client very soon. That thought might obviously be about solving the problem of needing to reply, but it’s often not clear why the thought arose at that moment. What was it in response to? Did something “complete”, as with finding a person’s name you were trying to recall before? If not, why did the situation arise in your awareness just then?

It turns out that you can trace your thoughts kind of like you can trace a conversation. (“How did we get to talking about beach balls? Right before that we were talking about sunscreen, and we were talking about that because… oh right, we were deciding if we should go to the store this afternoon!”) If you do this a lot, I think you’ll find one of two things in each case:

You’ll be able to trace the thought back to a prompt. Sometimes it’s an external prompt (like when someone asks you a question), and sometimes it’s an old prompt (like if you’ve been trying to sort out plans for an upcoming trip). But it’s a prompt nonetheless.

You’ll find it hard to trace the thought. You’ll draw a blank, or get bored with trying, or suddenly remember that there’s an urgent task you need to take care of, or get really tired or mentally foggy, or get lost thinking about something else, or get an uneasy feeling like you really shouldn’t keep trying to trace the thoughts back.

Why would the latter one happen? Well, one reason is maybe you’re just not used to examining your thoughts. Lots of people don’t notice that their thoughts have experiential texture (colors, shapes, sounds, weights, etc.): if I ask what the capital city of France is, the answer probably comes to mind easily, but if you don’t examine what comes to mind you probably won’t notice how you actually experience the thought. That’s very normal. It can take some practice to learn to notice these “mental sensations”. Without that level of internal sensory detail, it can be tricky to find the trail so to speak.

But another reason is that some mental strategies rely on parts of the strategy staying outside of your awareness. Self-deception being a type of example. If you think of yourself as “a sloppy person”, and the reason you started thinking of yourself that way was to have a self-image that could make your parents show you pity, the whole effort might break down if you were to become aware that that’s why you have that thought. So the mental program that produces the thought will also try to keep you from noticing why you think of yourself that way. Which means it’ll drag up some kind of noise or distraction whenever you try to investigate.

I say this to point out that while every thought is goal-directed, you might not be aware of the true goal. You might in fact be actively wrong about the goal. Thoughts aren’t for informing you of the truth; they’re the conscious part of a mental program that’s directed at solving a problem. Thoughts are accurate only to the extent that they need to be for solving the problem at hand. (E.g. if you’re trying to remember the combination code for unlocking your suitcase.)

And in general, thoughts about who you truly are don’t need to be accurate.

Identity is about tool use

I think the sense of self comes from the mind. And as with anything about mental behavior, it’s about solving problems.

Suppose I want a drink of water, and there’s a cup of water in reach. I can use my hand to lift the cup up to my mouth. That’s a pretty straightforward way to solve the problem. But it’s a little silly to say that I use my hand to grab the cup. Normally I’d just say “I’m picking up the cup.”

Here “I” includes my hand but excludes the cup. That’s where the identity boundary gets drawn.

But if I sleep on my arm wrong and my hand is numb, it becomes a thing. It’s kind of external to me. I can look at it like an anatomical object that’s attached to “me”. So now “I” excludes my hand.

Or in the other direction, if I can’t quite reach a light switch while sitting down unless I use a book I’m holding, then I’m still inclined to say that “I flipped the light switch.” I could say that I used the book to flip the light switch, but only if I’m trying to bring attention to specifically how I did it. Without that, “I” naturally includes the book.

Or for a more extreme example: if I mention a story where I’m driving downtown and I almost hit someone, I don’t mean that I almost rolled down my window and punched a pedestrian. Everyone intuitively knows that “I” includes the car I’m driving.

But if I lost control of the car, like if the steering wheel and brakes stopped affecting the car’s movement, I’m inclined to say I lost control of the car. I don’t typically say that I lost control of myself. Suddenly the car is an external object, rather than part of me.

In all these examples, I’m illustrating how identity is a way of tracking the difference between (a) what you can use to accomplish a task versus (b) what you act on in order to accomplish that task. The first category is part of the sense of self and is what first person singular pronouns (“I”, “me”, “my”, “mine”, “myself”) get applied to.

I want to emphasize that the thing about pronouns is an inclination. Identity is about what feels natural to include in those words. When I’d practice sword fencing in martial arts, it felt quite natural to say that I hit my opponent or that he hit me, even though it’s really the swords that hit our respective bodies. But if he knocks my sword off to the side, it feels very weird to say he knocked me off to the side. Which is to say, identity is moving very fluidly even at the pace of a sword fight.

Identity can even change mid-sentence. That’s pretty common when people use reflexive pronouns (e.g. “myself”). When folk say things like “I just couldn’t stop myself from saying that”, the parts referred to as “I” and “myself” are usually different. “Myself” was trying to say whatever it was, and the “I” part didn’t have the power to stop the “myself” part. But by the time the person says the word “myself”, they’re usually identified as the person who made the utterance.

In short, identity is how the mind tracks what tools it’s relying on right now.

I mostly don’t think about my keyboard while typing; it’s kind of subjectively “invisible”, the same way it’s “invisible” how I move my fingers to type. I just say that I’m writing. But if the keyboard started behaving erratically, it’d pop outside my fluid implicit sense of self, and I’d be looking at it as an external-to-me object while trying to understand what’s going on. The problem I’m solving has changed, so naturally who I am has changed.

Another way to see this pattern is to notice what it’s subjectively like when there’s no problem to solve. One example can be while watching a show on Netflix. You don’t need to do anything other than make sense of the story. So your sense of self can vanish. There’s just show-watching-ness going on. (But later when you need to explain what you were doing, your mind can retroactively interpret it as that you were watching the show, even though that wasn’t the subjective experience at the time.)

Some experiences of awe do this for me too. Like when viewing a vista, or admiring a sunset. There’s nothing I’m trying to accomplish, no problem to solve, nothing to figure out. I’m just enjoying my present moment experience. When I’m really struck by the beauty of the scene, it subjectively feels less like “I’m struck by” and more like being-struck-by just happens. There is no subjective sense of “I” at the time.

But if I’m sort of caught off guard by a blast of beauty mid conversation, and my friend asks me what’s going on, I might “come to” and reconstruct a sense of self. I need to explain what just happened for social reasons, so I task my mind with reinterpreting the scene. Then the “I” comes back into the story I tell of the sudden pause.

Meta: keep it practical

It’s normally hard for minds to track problem-free ways of being. If those ways of being are problem-free, then what good are they? What problems do they solve? They might even interfere with current problem-solving efforts by ceasing to care! So sometimes you’ll find that a mind will block access to “all is well” states of awe and no-self.

That’s a major reason why I started by pointing out problems that minds typically have a lot of trouble solving without sorting out identity issues. I’m suggesting that the no-self perspective can be useful for dealing with some of those sticky situations. I’m trying to spell out why, in a usable way, so that the mind has a reason to care about orienting to (and sometimes handing control over to) non-mind parts of subjectivity.

(I suspect that in the spirit of Iain McGilchrist’s ideas, I’m talking about conveying to the brain’s left hemisphere some reasons why the right hemisphere is important. But what I’m saying doesn’t depend on this picture of the brain. I just like McGilchrist’s model and notice that there’s a clear plausible connection to what I’m spelling out.)

I think it’ll be easier to understand the ideas I’m laying out here if you keep connecting them back to pragmatics. Are there problems in your life that seem to resist being solved? Do you have some of them fresh in mind? When you examine them, can you see how identity is a factor in at least one of them?

I haven’t finished the explanation, so I don’t expect it to be useful just yet. But I want to emphasize that the intention here isn’t abstract philosophy for its own sake. It’s very practical. If you keep the goal in mind (!), I think you’ll find the ideas easier to understand and relate to.

I bring up pragmatism at this point because typically when I start naming no-self experiences, many people will go kind of blank or get confused. I think that at least sometimes this comes from the mind objecting to what it sees as ideas that get in the way.

That’s a very sensible reaction. I don’t mean to say it shouldn’t happen. I’m saying that I expect you’ll get farther in following along with these ideas if you remember that the point is to improve your ability to solve problems, especially in cases that so far have been intractable.

Objects are for solving problems

I also add the above interjection because the last key point tends to create an even stronger reaction. Some mix of “That’s obviously false”, “That doesn’t make any sense”, and “What’s the point?”

I’ll try to address all that here. Just bear in mind that the point is practical. There’s a perspective shift on how to view the mind that makes some super sticky problems just… melt away. And it’s clear why, from inside that perspective.

So with that said:

The same way identity is about solving problems, so is object perception. A chunk of experience gets mentally tagged as a thing so that it can be accounted for and maybe affected or controlled.

There’s a kind of assumption in Western thought that objects are inherently real. I’m typing on a keyboard, which is really here. You’re reading these words, which are really in front of you. There are things in the world. We see them as such because we’ve learned to recognize what’s already there.

I basically want to suggest that this view is a simplification. It’s not really true. It’s just useful in some situations. But it proves to be systematically flawed in others.

Consider the apps on your phone. It sure looks like there really are apps there, right? You open your phone and there are the icons. You touch one to open the app. Real, right?

But there aren’t actually any apps in the phone. There are pixels lit up in specific patterns on a screen. You mentally interpret some of those pixels as “an icon”, but there’s no “icon” in the phone. There’s just circuitry.

The same is true for words. It’s not true that there are words here independent of all human minds. What it means for there to “be words” here is an interaction between reality and human minds. There “really are” words here in the sense that when you view this experience through that lens, you’re able to suss out coherent meaning, which you imagine is related to what some author intended to convey.

Westernized minds typically have a lot of trouble with this idea. They’ll typically object that however their brain is interpreting the situation, some interpretations are more correct than others. Yes, newborns can’t make sense of objects yet, but that’s because they haven’t yet learned which objects are really there.

I really am saying that no, this view of objective reality is simply false. That’s not how reality works. There are no objects prior to minds creating them to solve problems. There’s no “correct” way to parse reality into things. There are just more or less useful ways of viewing parts of reality as separable for given tasks.

It’s helpful for me to view a cup as distinct from a glass if I want a sip of water from it. It’s not very helpful for me to view the scene as an undifferentiated sea of atoms. So once I have a goal in mind, there are more or less “correct” ways of making sense of what’s going on.

But to a chemist, the difference between the cup and the table is pretty minimal if they’re both glass. And the difference is truly irrelevant to someone who’s trying to destroy the whole building.

I’m suggesting that the same way every thought is suffused with a goal, so is every object in your perception. You perceive objects for the sake of solving specific problems.

Or said more precisely: your mind carves reality into “this thing” and “not this thing” as a strategy for using “this thing” for some goal.

One hint of this view of objects is, again, in states of awe. When viewing a vista, I see a wholeness. I’m beholding the vastness of the view. (Or rather, there is beholding-ness.) With some subtle effort I can pick out a river and specific trees and so on. I might zoom in on a few objects and make sense of them and name them for a companion. But the default state is object-less-ness. There’s nothing I’m trying to do, so there’s no thing for me to do it with. My mind has no reason to create any thing.

Object rigidity

Just like with identity, this object perception is quite fluid. Minds are pretty good at sorting out objects in useful ways for simple physical tasks. Like how a chair can suddenly become a stool when you’re looking around for a way to reach a high-up shelf. You probably don’t even notice the carpet or the paintings on the walls or the shadows that the curtains cast on the floor. Your mind probably didn’t bother parsing any of those into objects at all. (Why? Because they don’t seem relevant to any current problems!)

Sometimes, though, minds can kind of get stuck on viewing part of reality as an object in a very particular way. Creative solutions that require de-parsing the object as such get automatically thrown out.

A classic example of this is the Duncker candle problem. (The below video is about 90 seconds long; for whatever reason it’s a video of a longer video.)

In many cases the issue is that the person just never thought to view the object differently. If someone had never seen anyone stand on a chair, they might not realize it could be used as a stool. But it’s usually no trouble to think of it that way once it’s pointed out.

But sometimes it’s very important to someone that they keep viewing something a particular way. For complex reasons I’ll get to in a bit, this usually shows up in social situations rather than physical ones.

Like whether a trans woman “really is a woman”.

A simple clarifying question I like to ask here is “…for what?” When something’s nature seems confusing, it’s helpful to ask what problem is being solved. Is a trans woman really a woman… when it comes to giving birth? No. When it comes to how they’re socially treated? Well, that depends on the social context and whether they’re “passing”. How about legally? That’s more complicated and is subject to ongoing debate, but right now under the second Trump Administration the federal answer is roughly “No.”

But it can feel meaningful to ask: are trans women really women, or not? What’s the truth here?

It turns out that the answer is reflexive. Which is to say, the “correct” answer depends on how the situation is viewed. So anyone who has stakes in this argument has some reason to claim that the answer is not reflexive, i.e. is instead objective and therefore should be viewed a particular way. That there’s an absolutely correct conclusion here, and that if everyone were to conclude something different then everyone would be wrong.

In this case, the political view is an attempt to steer where we all land, rather than an attempt to describe what’s objectively true. Although it works better if the people involved believe they’re just fighting for recognition of an objective truth!

Just like with the candle problem, this rigid way of thinking can make some problems unsolvable. Sadly, unlike the candle problem, pointing out the rigidity rarely helps, since there’s a social problem being solved with the rigidity.

And as a general rule, minds will not change their strategies unless and until they have a better way to solve the problems those strategies are for.

…which is very tricky when their current solutions constrain which solutions they’re able to even consider!

Social self

Minds tend to parse situations into things that interact. So if I’m picking up a cup, I’m by default inclined to think of “me” and “the cup” as separate objects.

Having a mental model of myself as a thing is actually quite useful. It lets my mind do recursive social reasoning. To be socially graceful, I have to distinguish between all of:

Whether Alice wants to go on a given trip.

Whether Bob wants to go on the trip.

Whether Alice thinks Bob wants to go on the trip.

Whether Bob thinks Alice wants to go.

Whether Alice thinks Bob thinks Alice wants to go.

Etc.

Likewise, I need a way of viewing myself so that I can be added to the mix:

Whether Alice thinks I want to go.

Whether Alice thinks Bob thinks I want to go.

Whether Alice thinks I think Bob wants to go.

Etc.

To think this way, I have to have a way of viewing myself sort of “from the outside” the same way I view Alice and Bob. And I need to view myself as distinct from, say, the floor or the sky or whatever, in roughly the same way as I view the other two.

So I end up with what amounts to a kind of little icon or model of “myself” in my mind, that’s of basically the same type as for other people.

I think that’s why images like this one can make sense:

It doesn’t matter whether you, or I, are one of the figures being depicted here. It’s kind of “from the outside”. It’s an objective depiction of a social situation.

When solving social problems, people often default to using this kind of mental icon for themselves. “I’m a Democrat” or “I’m a Catholic” is often (and I think usually) an assertion that an attribute they see being assigned to some other people should also apply to themselves. Where “themselves” here is about that mental icon.

Contrast with statements like “I’m happy” or “I’m tired”. Those are often statements from inside the experience, trying to articulate what the experience is actually like right now. Very different from “I tend to be a happy person”, which is pretty blatantly a statement from a vantage point outside the “I” who is being described.

The same way my keyboard is kind of invisible to me while I’m using it, so are these social icons. I tend not to distinguish between my housemate and my mental model of my housemate; I sort of project my impression of who he is onto the person standing in front of me. That process can go more or less poorly depending on how good a fit my model of him is for a given situation.

…although I hasten to add, “fit” here doesn’t mean accurate. How could I ever know? What I mean is, when I use my mental model of my housemate to guide my interactions with him, how well does that go? Do I get the results I’m expecting? I don’t think there’s a correct model of someone, the same way there’s no correct way to parse the world into objects. The question is whether the model is fit for a given purpose.

If I run into object rigidity with how I’m viewing someone — which is to say, it’s important to my mind’s current strategies that I view that someone in a very particular way — then there can be trouble. Like if I’m in a romantic relationship but my view of my partner is a bad fit for changing some of our painful ways of interacting. If I can’t set the model aside enough to see her afresh and develop a new vision of her, then I can’t change, and our dynamic can’t change. This pattern is part of where stubborn relationship problems can come from.

And it’s important to add, this pattern isn’t due to some bad habit of being stuck or whatever. Model rigidity, best as I can tell, is always strategic. Minds don’t hobble themselves for no good reason. If the mind fights changing its model of someone, then there’s some strategic reason why it’s important to view them that particular way. You cannot change such a mind without giving it some different way of solving the underlying problem.

Because my social icon for myself has the same properties as my social icon for others, I can run into exactly the same dynamics here. My social sense of self can be invisible, sort of projected seamlessly onto my more immediate experiences of being. It can be more or less fit for a given purpose. And sometimes (such as with self-deception) it can become very strategically important that I view myself in a particular way even if it’s not fit for a given purpose.

In sum

At the risk of repeating myself, here again are the components of how I view the mental sense of self being created:

Minds are problem solvers.

Minds create a “me”/“not me” distinction to track which tools can be used (“made invisible”) versus what is to be affected. This sense of identity is always with respect to a task.

Minds also create the impression of things. Object perception is always with respect to some goal.

In particular, minds create mental objects (what I sometimes call “social icons”) to do social problem solving, and have to create a social icon for “myself” in order to be included in social thinking.

Some social problem solving can result in object rigidity, i.e., a strategic need to view an object or a person in a very particular way.

All of this can combine into a sense of self that’s (a) seen as separable from the rest of reality, (b) is a bad fit for solving some of your problems, and (b) nonetheless pragmatically hard or impossible to change directly.

Solving problems that fight back

I think this paints a pretty good picture of where some sticky problems (i.e. problems that strategically fight being solved) can come from. The basic issue comes down to the cause of object rigidity: there’s some reason why you have to view a thing, or someone else, or yourself, in some particular way. So if that framing is a bad fit, you’re stuck with the problems of that bad fit unless and until you can solve the underlying problem differently. And pragmatically speaking, that underlying problem is basically always a social problem (as opposed to a physical problem like being thirsty).

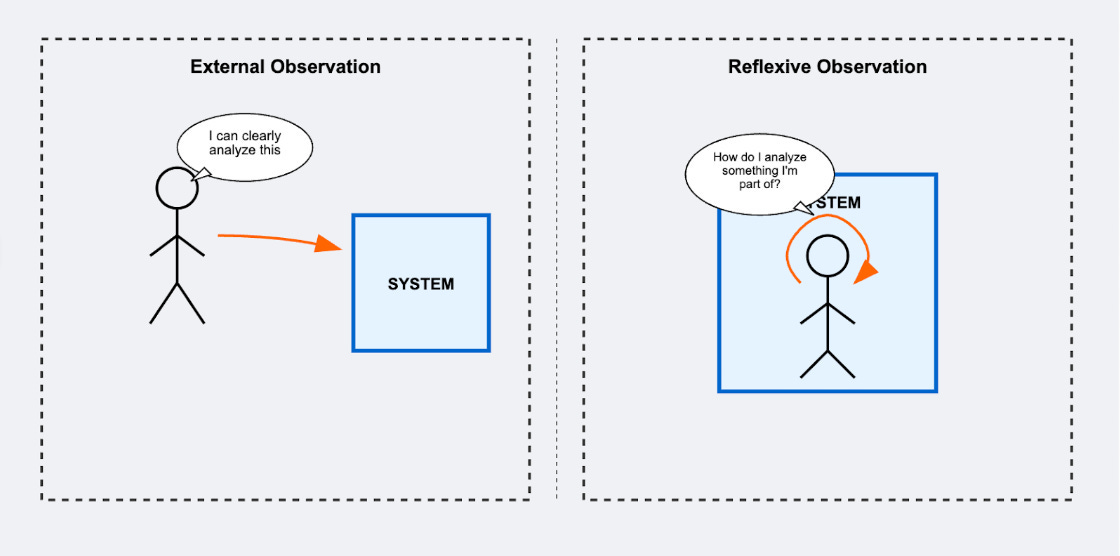

I think the Buddhist aim of realizing no-self is at least partially a general attempt to fix this meta-problem. It turns out that the mind’s model of self is fundamentally incoherent: minds have a lot of trouble making sense of reflexive situations they’re part of, so their models of themselves are always flawed in some critical way.

This challenge shows up in the model of self I’ve given so far, in fact. I’m treating the mind as a thing, and the mind’s user (“you”) as a thing, and naming their interaction. But there’s no way for the mind to stand outside itself and observe itself.

Typically, minds deal with reflexive situations by assuming they can view those situations from the outside. That works fine when you’re trying to make sense of a foreign economy, or someone else’s marriage. But it fails spectacularly when trying to analyze systems that that very mind is part of!

A lot of Buddhist insight meditation strikes me as basically staring at this incoherence and prompting the mind to make sense of it until the mind sort of gives up on its basic strategies. Object rigidity with respect to the social self sort of falls away because the underlying problems that the rigidity is solving are seen as meaningless.

My guess is that there are probably ways of implementing this strategy much more efficiently.1 But we don’t have those methods yet. So in the meantime I want to gesture at some alternatives.

The main unifying theme is that the underlying problem causing object rigidity has to be solved differently. That’s almost always a social problem. For instance, that’s how I came up with some unusual solutions to signs of self-deception. I reasoned basically like so:

All mental behavior is strategic. When there’s a strategy that seems to create problems for the person, but they fight against attempts to change the strategy, that implies there’s some social problem being solved for which the current issues are acceptable side-effects. If I look at self-deception through this lens, what do I see? What could be socially useful about self-deception?

The result was the idea of the hostile telepath problem. And it suggested some odd interventions, like that giving yourself permission to hide or even lie about your internal experience can clear recurring mental fogginess. The reason being that some mental fogginess is a solution to a hostile telepath problem, and “occlumency” (i.e. the skill of hiding your internal experiences from others) is an alternative solution that might work even better.

The issue, of course, is that if part of your current strategy requires that you be unaware of the original problem, then coming up with alternative solutions can be quite hard. You certainly can’t do it by just consciously thinking about it!

I suspect this is why some methods of “trauma processing” mysteriously work when they do. They’re often helping you to notice that the situation you were trying to deal with isn’t around anymore. But it has to be indirect, because the strategies you implemented won’t let you be aware of them. So sometimes you can get clear on why you have the problems you do only after you’ve solved them somehow.

For related reasons, it can be helpful to have someone else guiding you through a process of finding alternative solutions. Since they are (hopefully) not subject to your current need to keep your strategies hidden! But this is very tricky business, since the underlying problem is almost always a social problem of some kind, and it’ll often apply to your friend or coach or therapist or whoever it is.

I’ve solved some special cases of these problems quite elegantly. I hope to talk about those cases quite soon. They relate to what a colleague & friend and I refer to as “Original Spin”. I also have one quirky approach laid out in my article on hostile telepaths.

But this piece is long enough, and I’ve run out of time to work on it this week. So I’ll leave this sketch here and invite your own exploration:

If you apply this lens to your own situations, what do you see? What underlying problems might be there? If you get mentally fogged or distracted while trying to answer that question, how might you explore alternative solutions without risking breaking the ones you already have?

And germane to subjective science: what “sticky” problems do you observe that you can tell do not have the structure I’m describing here?

By legend, the Buddha and some of his disciples were able to pretty reliably lead people to awakening over the course of a few years. That’s not something modern Buddhism seems to know how to do. So if there’s truth to those legends, then some effective teaching methods have been lost over the millennia. And it suggests that maybe there really are much, much more effective ways of enacting Buddhist solutions to these problems. So I’m hoping that subjective science can do for Buddhist awakening what objective science did for medicine.

> When I’d practice sword fencing in martial arts, it felt quite natural to say that I hit my opponent or that he hit me, even though it’s really the swords that hit our respective bodies. But if he knocks my sword off to the side, it feels very weird to say he knocked me off to the side.

I think the grammar allows you to "hit your opponent" using a sword, still treating the sword as an object (or tool), not part of yourself. The reason you don't say "I hit my opponent with my sword" is simply that the sword part is inferred from context, not that it wouldn't suddenly exist as an object separate from "me". So justifying "tools are part of 'I'" from linguistics doesn't feel very natural.

The car example is much better. When driving, the car becomes part of the body. Physicality of the body isn't important: when playing a virtual rally game, the body is partly virtual. What's important is the tool aspect: do I control it directly and voluntarily, or do I need to act on it indirectly.