Subjective Science

We can study the sacred. For real.

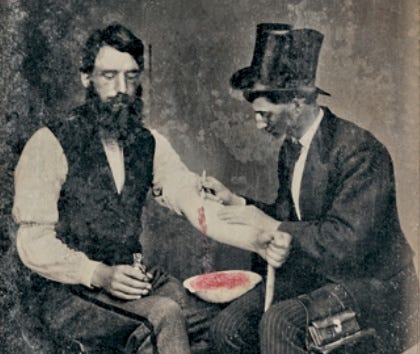

Up until the late 1800s, the main Western theory of medicine had a decent bit of similarity to traditional Chinese medicine. The core idea was humorism: that human bodies had four fluids (the humors) corresponding to the four Greek elements (Earth, Fire, Air, and Water), and that health problems came from imbalances in these fluids.

So for instance, someone who was sweating from fever might be thought to have too much Air (because Air was “hot and wet”), which corresponds to the humor of blood. Hence bloodletting as a solution.

This was the dominant medical theory in Europe for centuries. Today we usually think of it as pretty backwards to weaken someone who has a fever by making them bleed. So why did the practice survive for so long?

Well, it turns out that bloodletting sometimes can make it feel like a fever is backing off. A doctor (or a barber) would conduct the procedure, and the patient would feel cooler, which seemed to validate the model that the fever came from too much blood.

We now know that the patient merely feels cooler because losing blood can create an emergency response in the body. Weakening someone who’s fighting off an infection is actually a really bad idea. But often enough someone would recover despite the medical intervention — at which point most people would attribute the recovery to the bloodletting.

So it sure looked like it worked!

I think we’re basically at this stage when it comes to social science. I’m thinking particularly of mental health therapy (or “coaching”) and spirituality. People have very strong opinions about how to “heal trauma”, or the nature of “the ego” and why it’s important for it to “die”, or how to raise emotionally healthy children, or what makes for a good marriage, or what policy would solve some societal problem if it were put into law. When the intervention seems to work, the success gets attributed to the intervention. When it doesn’t, there’s nearly always some explanation for why that keeps the original theory alive.

This approach misses the core insight of science.

Not to say there’s nothing to these ideas! Even bloodletting turned out to be genuinely helpful sometimes. (It could reduce excess levels of iron in the blood, for instance, which really can help deal with or prevent other issues.) People were successfully solving tricky problems tens of thousands of years before the invention of science.

Like cathedral building: we were able to work out the idea of flying buttresses centuries before Newton. And that solved a real problem! Suddenly cathedrals could have glorious amounts of light.

And yet, no pre-scientific advances in cathedral design were ever going to let us build skyscrapers or rockets to the Moon.

But somehow, the single idea of science let us not only build those, but also master electric power, and systematically manufacture steel, and invent vaccines, and set up satellites to develop GPS, and create engines that could power machines for us. All in the same 300 year period. A mere fraction of the time we’d been working on cathedrals.

We just haven’t seen anything like that kind of advance in terms of subjectivity. We don’t have a “vaccine” for mental illnesses, or a “steam engine” for meditation, or a “GPS” for governmental design.

What we have instead sounds an awful lot to me like humorism.

There have been attempts to fix this before. An example is behaviorism, which tried to turn psychology into a natural science by making everything objective. Behaviorism gave us some pretty powerful tools like masterful animal training. But it spectacularly failed at most things we really care about, like good education and sorting out interpersonal conflicts.

I think the problem arises from two related issues:

We misunderstood what the insight of science actually was. We’ve come to think it’s tied to objectivity. I think that’s simply incorrect. Science is an insight about how to relate to understanding. Objectivity is just the domain we got really good at applying science to.

Objectivity works incredibly well when examining objects. But the most interesting aspect of people is precisely the ways in which we are not merely objects. In particular, unlike objects, people are reflexive — meaning that our nature changes based on how we’re viewed. Things like how well a date goes depends a lot on how well the pair expects the date to go. Objective scientific methods tend to stumble or outright fail in contact with reflexive phenomena like this.

It seems to me that these issues are straightforward to fix. That possibility excites me a lot. It means that we can maybe have a real science of wisdom and wholesomeness. Something that makes everyone who comes into contact with its ideas more vibrant and kind and clear-minded. What would wholesome science be like, building engines of compassion and clarity that can then empower our culture to grow into wonderful ways of being?

I don’t have a full answer to all that. It’s pretty critical that it’s not all up to me.

But I think I see a key piece of how to get there.

I’d like to take a shot at sharing that piece here.

The soul of science

It seems to me that science is a process of evaluating and refining explanations. It’s not about some particular methods like RCTs or statistics or data-gathering. Those are tools. The soul of science is in the pressure it puts on ideas to explain the world clearly in ways that sort of stick their neck out.

More precisely, I think of the core process of science as having two parts:

Come up with explanations that are easy to disprove if they’re wrong.

Then give them a chance to be disproven.

That’s it. That’s science.

Crucial experiments

There are lots of adjacent processes that often get called “science”. Things like counting the calories in the food you eat. Lots of people will say that this is “doing science” with your diet.

That really isn’t. It’s just measuring something. People have been measuring things for tens of thousands of years.

Actually doing science would look more like so:

There’s this explanation for obesity that it’s “calories in = calories out”. So if you can maintain a calorie deficit for a while, you should lose weight. Meaning that if you hold a calorie deficit over a reasonable amount of time and you don’t drop your weight, then the theory is false.

That’s the disprovable explanation. It allows you to perform what’s called a crucial experiment: you can run a calorie deficit for a while and see whether you lose weight. If you don’t, that disproves the theory.

In practice, people don’t really care that much whether this theory is disproven. It would for sure be strange if it were! It’s based on thermodynamics. But the hard part is more like using the theory to lose weight. Basically a question of applied science. Many people cannot force themselves to maintain a calorie deficit, get down to an ideal weight, and then maintain a calorie in/out balance to maintain that weight.

To which there’s a common refrain (maybe more in the cultural groundwater at this point — I mostly don’t hear people saying this anymore):

“It’s just a matter of willpower.”

Like failing to stick to a diet and exercise plan is a failure of will. Like the person just isn’t trying hard enough, or maybe doesn’t really care.

Through the eyes of science, this is something that could become a real theory. But it’s missing a pretty key element: how would you disprove it?

That’s not just a formalism. It’s really key. If there’s no way to challenge the idea, we can’t know how good its fit to reality is.

I mean, here’s a counter theory:

Everyone is born with a kind of natural set point of weight kind of programmed into them throughout their lives. That’s why they tend to have the same obesity and scrawniness patterns throughout their lives that their family members do. Trying to force your body to change in defiance of its set point is actually really unhealthy. It’s possible some toxic things in the environment can cause those changes, in which case sorting out environmental toxins is pretty important so you can reach a healthy weight. But starving your body to get down to a weight that you think is good is usually unhealthy.

Sounds plausible. More detailed than the “It’s just a matter of willpower” theory.

How shall we decide which one is a better fit to reality? Argue about it? Point at authorities who agree with one view and disagree with the other? Refer to sacred texts? Trial by combat?

The key insight of science is that there’s a way to pressure ideas to get good at telling useful truths. Making explanations killable and then trying to kill them forces them to survive by being good at explaining things.

The scientific answer to the weight loss debate is to ask how we could make the ideas specific enough to make falsifiable predictions. And then we’d look.

For instance, what does it mean for it to “be unhealthy” to deviate from one’s weight set point? What does that look like? Is it a subjective feeling? Is it about measurable things like blood pressure? Is it a reference to overall morbidity, meaning we could detect “unhealthiness” only at the population level by looking at how many people live or die over some period of time?

Let’s suppose the theory says that biological markers of health like blood pressure and cholesterol levels would get worse due to deviation from the set point. We now have a disagreement in prediction between the two ideas:

If losing weight is purely a matter of willpower, then lowering the willpower requirements to stay with a calorie deficit should work, and people should get healthier.

But if losing weight is a matter of deviating from a set point and that’s why there’s resistance to doing it, then we should see that forcing weight loss should result in people getting less healthy.

Now we can do a crucial experiment. One of these ideas will die in the crucible of looking at reality.

This is the basic logic of science. Over and over again, you (a) try to make your explanations specific enough that they necessarily predict some outcome in some situation, and then you (b) try to set up that situation.

Making theories disprovable

Theories that are easier to disprove are more precious. They tell us more as a result of their survival.

There was an old idea about how motion worked before Newton came up with his laws of motion and gravitation. It was the dominant theory for centuries before Newton’s insights. The idea was basically that the Greek elements had a natural order with Earth at the bottom, Water above it, Air above that, and Fire at the top of the four. So rocks fall because they’re mostly Earth and they’re trying to return to the sphere of Earth, which is below Air. Whereas bubbles rise because Air is above Water.

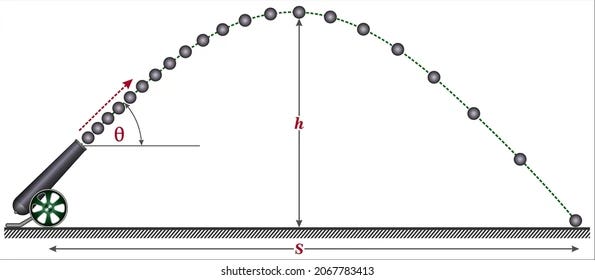

How then can we throw a stone up into the air? Why doesn’t it just immediately fall? Well, clearly living creatures have some kind of ability to add a force or intention to inanimate objects. So we sort of imbue the rock with that intention when we throw it. But as our intention kind of leaks out of the stone, it starts to fall. Hence it goes through a kind of arc in the air.

But what’s the shape of the arc? Is it circular? Is it some other shape? Why isn’t it a kind of “V” shape where it goes in a straight line until it abruptly runs out of living force and sort of “dies” and drops straight to the ground?

The old theory (Aristotelian physics) could be massaged to account for any of these. But without actually looking at the trajectory of a projectile, it wouldn’t be able to predict the shape of the arc.

Newton’s physics are far more constrained. They absolutely require that a stone thrown into the air follow the path of a parabola.

So that’s interesting. It means that if we measure the paths of a bunch of different thrown objects, if any of them clearly deviate meaningfully from a parabola, we will have disproven Newtonian mechanics. But not Aristotelian physics.

So what are we to make of the fact that many, many such measurements exactly accord with the parabolic arc?

Well, it means that Newton’s theory is more useful as an explanation of what’s going on. It gives the same predictions as Aristotle’s physics, but more narrowly. It’s a highly constrained theory. Meaning that we learn more from its surviving crucial experiments.

What’s so special about this process?

So why would this particular approach to ideas work so well? What’s so important about making ideas disprovable? Surely there are some ideas that are true and important but hard to disprove, right?

(To that last question: yes, of course. But that’s precisely why wisdom practices are so tricky to distinguish from nonsense! Why dangerous guru dynamics are possible, for instance. I’d say that true and important ideas particularly about wisdom can be hard to disprove so far, and that one day — hopefully soon — we’ll care a lot about changing that ASAP.)

I really want to give a full answer to this question sometime. About why this particular orientation to ideas is so important. But a detailed answer is worth its own full post, and I haven’t written it yet. So I’ll try to provide just a quick sketch here with some pointers for now.

It turns out that ideas obey evolution. That’s not a scientific finding; it’s more like a logical necessity. It wouldn’t mean anything coherent for that claim to be false.

Most ideas undergo “wild” evolution. This can produce, for instance, the mental equivalent of parasites. (Have you ever seen someone go kind of crazy due to contact with an idea?) I think CGP Grey gives a great breakdown of an example application of the logic. If you have time and inclination, I think it’s worthwhile to spend the 7 minutes it takes to watch this video:

A key insight here is that what we consciously believe mostly isn’t about what’s true. It’s about what encourages those ideas to survive. That’s what they evolved to do. Making us think true things is just one strategy ideas can use to survive.

Science is a kind of evolutionary pressure on ideas. It’s making it advantageous for them to help us understand the world better. We do that by encouraging ideas to explain the world to us in ways we can check.

That “in ways we can check” part is really critical. If we are happy with ideas that feel compelling, then ideas will evolve to be compelling. That becomes their evolutionary angle of advantage. That’s why, for instance, Flat Earth conspiracy theorists are able to convert people to their view and remain unpersuaded in the face of compelling evidence: conversion and inoculation against competing ideas is precisely how Flat Earth ism can survive.

So if we want to “domesticate” ideas, we have to apply an evolutionary pressure to them that makes them actually “friendly” and helpful to us, systematically, over time.

The key insight of science is that we can actually do this. If we get ideas to explain the world in ways that necessarily require very specific predictions, and those predictions pan out, then we can use those explanations to solve problems. If those explanations ever fail, they “die”, and we seek new ones that can explain and predict everything the defunct theories did without the “deadly” flaw.

Without this kind of “artificial selection”, ideas evolve to survive through us based on whatever we’re paying attention to about them. Things like creating feelings of insight, or making us outraged, or keeping us numb and checked out while we mechanically follow patterns that make sure they replicate in our children. Some will give us benefits too, but only incidentally, or when their survival strategy happens to hinge on their being helpful.

But with science, we can systematically move toward clear-mindedness. We can actually understand the world in ways that matter.

…including how science works. Science, clearly seen, is reflexive.

There’s a lot more to say about this, but I’ll leave it here for now.

Objective vs. reflexive

So why has science converged so hard on objectivity?

I think it’s basically a simplification. We can loosely split up everything we observe into two patterns:

Objective: Stuff that’s there no matter how we look at it. Rocks and trees and the Sun. This is the domain of Philip K. Dick’s quote, “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”

Reflexive: Stuff that changes its nature depending on how we look at it and who we are when we’re looking. Things like whether a date will go well, or whether a vague horoscope “is accurate”, or the true meaning of a Rorschach ink blot test.

Most of the stuff that deeply matters to the human heart is reflexive. Falling in love is a kind of dance with another person: it is absolutely essential that they be responding to us, and how they respond to us is based on how we respond to them. Poetry touches us because of how we relate to the material, which is related to things like meter and word choice but fundamentally isn’t about them. Spiritual experiences feel profoundly meaningful, and we care about that, even though the basis of knowing they’re meaningful is the simple fact of our having experienced them.

I’m particularly interested in questions of wisdom: what does it mean to skillfully live a good life, in ways that enhance others’ ability to skillfully live good lives? What encourages wholesomeness, given that how I try to find an answer to that question can itself be more or less wholesome?

I think it’s absolutely possible to approach these domains with science. I think it can be beautiful. I suspect it has to be.

But it does require loosening the bond of science to objectivity.

Objective science is easier

Objective stuff “moves around” less. So it’s easier to come up with easy-to-disprove objective explanations and then test them. Science is just way, way easier to do on non-reflexive things.

Like when Einstein came up with general relativity. That explanation of gravity predicted that the planet Mercury would move a bit differently than Newton’s theories said it would. That meant we could actually look and possibly disprove Einstein’s idea. But instead reality disproved Newton’s.

It did not matter what Einstein’s mood was. The planet Mercury wasn’t going to vary based on people testing it. The authority of people who agreed (or disagreed) with Einstein had no bearing on what we’d find. Gravity isn’t shy such that it changes what it does when tested.

So Einstein’s theory didn’t have to account for how the theory itself was presented. He could just state it, and we could test it. And then we discovered that his idea was a better fit than the one we had before.

But we don’t have to avoid reflexivity. It’s just easier to do science on things that aren’t reflexive.

Which is to say, on objective things. On objects.

Subjectivity is reflexive

Some stuff necessarily has to be explained reflexively. Meaning that the very act of explaining them is often part of the phenomenon being explained.

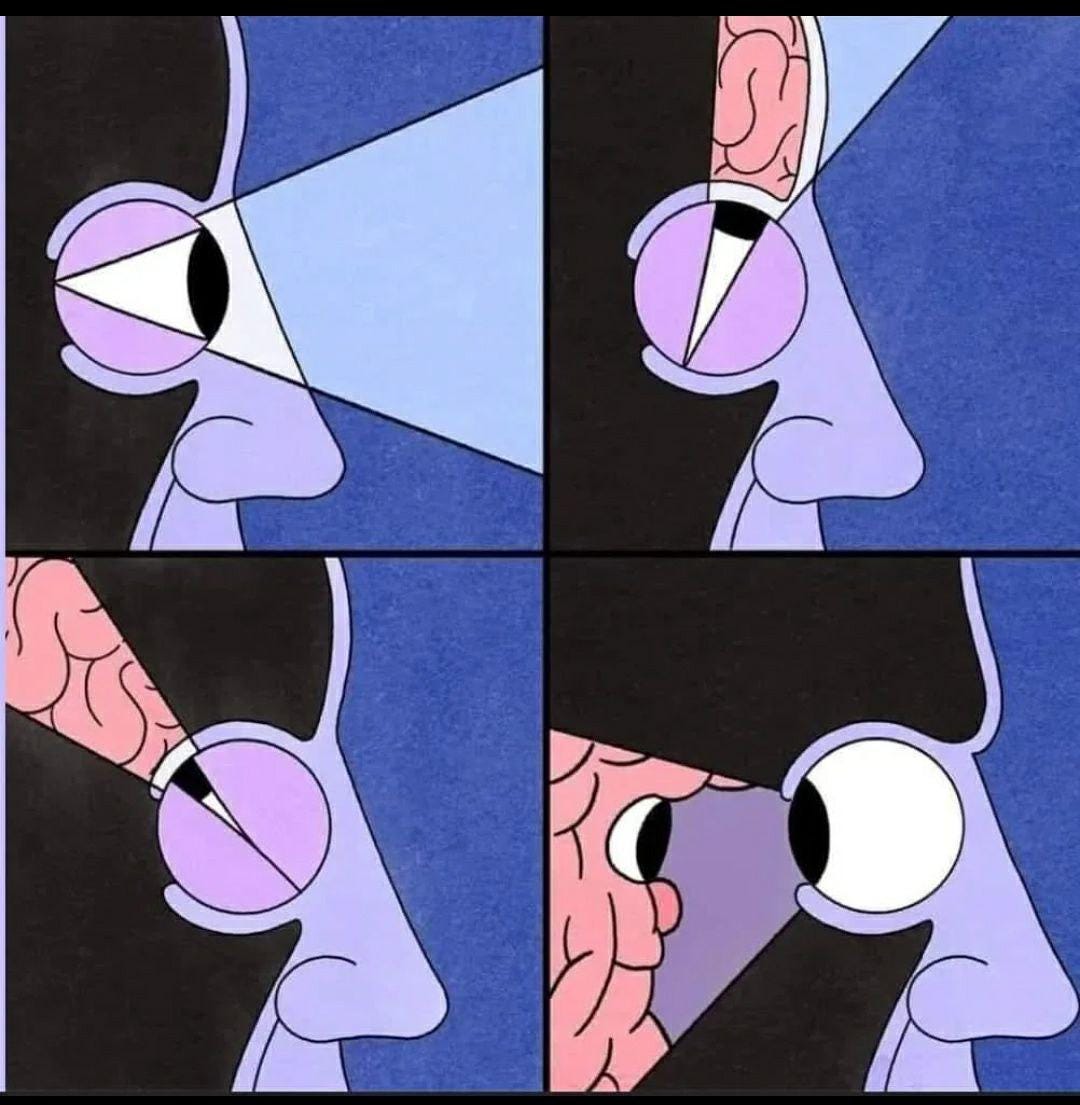

A vivid example here is any theory of the self. The moment we say “the self”, there’s some inclination to implicitly think of it (!) as a thing that you (!) might be able to look for and find.

But if you are looking at it, then who’s looking? What are they looking at?

The thing we’re calling “the self” is you. You can’t look at yourself from the outside. The very thought is incoherent!

Which means that if you come up with some kind of explanation about your innermost nature, that explanation needs to account for how you relate to that very same explanation as you’re looking at it.

I think there are some theories like this. Some Buddhist ideas are pretty good along these lines. The cluster around “emptiness”, “no self”, and “dependent origination” strike me as something that could be made clear enough to be easy to disprove if it’s false.

(Sadly the “easy to disprove” part isn’t very prevalent in most Buddhist contexts I’m aware of. They emphasize “Come see for yourself, don’t just take my word for it”. And I think that’s very good. But many places don’t lay out the claims clearly enough to be disprovable. Instead there’s always room for people to have “misunderstood the dharma” or have made errors in their meditation practice across years. This is the kind of stuff that feels to me like a spiritual version of humorism.)

Objectivity doesn’t define what’s real

Because objective science was so successful at mastering objects, people started conflating “objective” with “real”. As in, asserting that anything that can’t be made objective isn’t real.

Which weirdly would imply that people either (a) aren’t real or (b) are just objects.

That’s a very weird place from which to start looking for explanations of human nature. It’s not a promising angle for exploring wholesomeness. The basis of human connection is fundamentally reflexive: I see you seeing me seeing you. How on Earth are we going to adequately explain that if we treat it as incidental to objective stuff?

I think this is where the “hard problem of consciousness” comes from. The issue arises if we view consciousness as something objective and try to explain it objectively. That’s literally impossible. It’s basically a confusion made of words. What would it mean for consciousness to behave a certain way when no one is experiencing or interacting with it?

A key challenge is that objective science requires factoring out the first-person perspective. We remove the scientist from the thing being studied. Which means that if you want a science of first-person perspective, you cannot rely primarily — let alone entirely — on objective methods. The whole approach is gibberish. “First-person perspective” isn’t an object you can look at from the outside!

This situation is no trouble if we allow that reflexivity is real too. That falling in love means something even though it’s kind of self-defining. That wisdom exists even though we aren’t really sure how to define it and maybe cannot objectively do so.

That people are real. That experience matters. That relating to others as “I and Thou” is meaningfully different from seeing them as “it”.

Bad wizards

Now, I want to offer a thought experiment. Please bear with me here.

Suppose that astrology actually does work quite well, but that it does so reflexively. That it’s basically a tool for honing the intuitions of the astrologer so that they can very effectively cold-read their clients and provide subconscious nudges in ways that actually meaningfully help them.

The catch is, the tool works only if those involved believe it does.

If an objectivity-minded skeptic comes along and tries to show that the tool doesn’t objectively work, they might succeed — in part by breaking the tool.

If they then go around publicizing how they’ve “debunked astrology”, that makes the tool less likely to work — which will seem to validate the skeptic’s claim that there was nothing to it!

I’m reminded of the headline I saw years ago, referring to a 2010 medical study:

“Placebos found to work even when subjects know it’s a placebo”

…to which my immediate thought was

“Well now that’s true!”

Because if there’s a reflexive dimension to the placebo effect, then we should expect that telling everyone that it works this way will cause it to work this way.

The reverse could have in principle happened instead: someone could announce that placebos have been found to stop working once patients know they’re getting just a sugar pill. At which point that would become more true.

I’m also reminded of a friend who went to a doctor who warned “If you don’t get your stress under control, you’re going to have a heart attack or a stroke.”

When people refine their objective thinking to the exclusion of the reflexive, they can become very bad wizards. Casting curses willy-nilly with no clue what they’re doing. Often insisting that they can’t possibly be having the effects that they obviously are.

I’m really hoping we can develop wider awareness of both how science works and of reflexivity, so we can end the accidental gaslighting that follows from insisting that only objective things are real. We don’t have to choose between science and spirituality. We don’t have to fake their union. They can be the same thing.

I think the current split between the two is related to why astrologers work so hard to keep their art unfalsifiable. I do think there’s some real value to the discipline. I see it helping some people live much more full and happy lives. That matters. I don’t know the underlying mechanism, or how reliable it is or isn’t. I haven’t done good science on it yet. But it makes sense to me that if you have a seemingly good reflexive artform, and someone wants to beat it to a pulp with their objectivity cudgel, you might (perhaps subconsciously) make it hard for them to hit.

We just end up with the misfortune that it also makes science harder to do with the art. Which means the wrong ideas “breed” and over time the art itself becomes diluted and its true value starts to fade.

It doesn’t have to be this way. I think we can recognize that self-fulfilling prophecies are real, that some specific situations have that nature, and then use that recognition to intentionally predict the world that we want.

Kind of like choosing that placebos work because we expect them to.

And then it becomes possible not to curse ourselves into an objective dismissal of beauty, meaning, and the sacred. We can instead cherish them, and understand them, and come to embody an exquisite and glorious world together.

Needed: subjective methods

Objective science is way ahead of reflexive science. We’re just barely getting the latter into a coherent paradigm.

But I think we’re here. I think we’ve got the foundation now.

For instance, I think the model I gave for self-deception is a scientifically good one. It makes specific predictions about how certain subjective shifts should change certain subjective states. The idea is disprovable. It’s just hard to objectively disprove. The method of disproof is more like:

Understand the model well enough to map it to your subjective experience.

Notice which experiments could be crucial (i.e. could disprove the idea, or at least could strongly suggest it’s wrong, if it is).

Conduct those experiments inside yourself.

At which point you can tell whether the idea (as you understand it) has been shown to be wrong.

The tricky part is that self-deception might make it hard to think through the logic of the experiment. So your test has to account for that reflexive element.

But it’s quite doable. And in my experience it’s very striking when, say, someone’s mental fog very abruptly clears once we establish a good “occlumency shield” for them. That doesn’t prove the idea is right; that’s not how science works. But it’s quite meaningful if and when it survives that spectacularly.

Importantly, you can’t actually know that the model is correct for you. You might have a different understanding of it than I do. So even if I’ve done dozens of crucial experiments and found that this overall explanation works quite well, there’s still an important gap in your understanding.

Also, I could be BSing you, or myself, totally unintentionally.

So while I can give you the model and claim to you that it works, the actual scientific transmission is to give you a means of falsifying the model if it’s wrong. So basically making it easy for you to tell whether the experiments really are crucial and then to replicate them for yourself.

I think this is a good example of a subjective method (as opposed to objective methods): sharing crucial subjective experiments (including why they’re crucial) so others can replicate them.

To some extent I feel like I’m kind of brute-forcing the obvious solution here based on analogy. My guess is that there are more elegant subjective methods possible.

At this point I want to emphasize that this is a project that you can engage in. Science has never been about institutions or academics; that’s just how we formalized objective science, in part because objective crucial experiments often require a lot of materials and literal physical energy. But if you really get the soul of science, and you work on carefully tracing the reflexive reasoning of your subjective experience, you can come up with legitimate scientific experiments that can bring the clarity of the Enlightenment into your inner world.

This project is necessarily open-sourced. There are no gatekeepers here. No one granted me some official authority; I’m giving you the same keys I have.

Have fun with it!

This is great. The PKD quote about reality not going away when you stop believing in it also came to mind for me in orienting to the reflexivity thing.

It seems to me that we need a similar quote that captures the way self-fulfilling things also have a reality to them. I almost stop wanting to talk in terms of truth and more in terms of... stability? Reflexive stability? Of which singular objective truth is a degenerate case.

I talk a lot about "trust as what truth feels like in first person"; to some extent trust might be this thing; it can have this reflexive stability property.

But here we potentially get multiple mutually-exclusive attractors, none of which is more true than the others, but if we can relax our current view enough to consider the other possibilities, we can assess them not in terms of their stability property but in terms of their usefulness to us. At which point two different people/groups might have two different coherent attractors. It opens up a pretty big can of worms, but it's also exciting in terms of true plurality—not relativism where things can't be compared/judged, but allowing for different standards of comparison/judgment, within which some things ARE better/worse.

I really liked reading this, thanks for writing it! "One of these ideas will die in the crucible of looking at reality" was a very evocative sentence for me that really got me looking around at everything with fresh eyes