Tools that Enrich Us

Creating ease and getting stronger are often at odds. How do we want to navigate that tension?

A few years ago I stumbled across a tweet that pointed out a distinction. It’s stuck in my mind ever since. And it’s getting louder in my awareness as I watch AI become more widespread. I think we could use our new marvelous tools in ways that greatly enhance what’s profoundly beautiful about being human. Or we can use them to impoverish our souls. I imagine we’ll be at greater capacity to choose if we notice we’re making such a choice, moment by moment, use by use.

So in this essay I’d like to name that distinction a few different ways, and point out a tradeoff between them.

Make us smarter vs. make us dumber

The distinction starts out as “tools that make us smarter vs. tools that make us dumber”. I’ll adjust that framing in a moment but this is how I want to start talking about it.

Here are a few quick examples:

Arithmetic: abacus vs. calculator. Learning how to use an abacus trains your brain to internalize it. Arithmetic becomes faster and more reliable over time, and the mechanisms behind why different strategies work become obvious and intuitive. Eventually you don’t even need the physical abacus anymore. Whereas with a calculator you will magically, reliably, and instantly get the right result as long as you give it the right input. The price is that even if you were pretty good at mental arithmetic once upon a time, if you keep using a calculator (or “Hey Siri, what’s twelve times six?”) then by default those mental skills sort of fade away over time. And you will always need a calculator for math: it never becomes part of you the way an abacus does.

Navigation: maps vs. GPS. Back in the 20th century, we’d have to use paper maps to figure out how to drive somewhere. We’d write down directions for reference, often needing to steal a glance at our sheet while driving. The result was that generally if you drove somewhere two or three times you’d know how to get there without directions. And typically you learned the lay of the land (or city) from doing a few such trips. Whereas today you just plug the address into your phone and follow its step-by-step directions without having to learn or remember anything. Asking someone for directions is mostly useless today because folks’ sense of how to get places has atrophied: no more “Turn left at the gas station, then look for the bird-shaped bush on the right” type instructions. But now our tools let us account for traffic, road closures, etc. So we’re more effective on net even if we’re less competent without our phones than we used to be.

Memory: mnemonics vs. search. If you want to remember some facts, one strategy is to use a set of memory techniques. Things like the mnemonic link system and spaced repetition. Another strategy is to just look it up with Google or an AI anytime you need the info. The former strategy is more energy and time intensive but makes the knowledge immediately accessible within you. The latter makes you more dependent on external sources of data and is less likely to integrate into your habits of thought. But you do get access to vastly more knowledge than our ancestors would have ever had a chance to memorize.

There’s another very famous example. In Plato’s dialogue Phaedrus, Socrates tells of the Egyptian god Thoth1 presenting his invention of writing to the god-king Thamus:

But when they came to letters, “This,” said Thoth, “will make the Egyptians wiser and give them better memories; it is a specific both for the memory and for the wit.”

Thamus replied: “O most ingenious Thoth, the parent or inventor of an art is not always the best judge of the utility or inutility of his own inventions to the users of them. And in this instance, you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a quality which they cannot have; for this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.”

In other words, Thamus views writing as a tool that makes people “dumber”.

And in some important sense he’s correct! Cultures did in fact see their arts of memory decay as literacy spread. The same effect became even stronger when search engines like Google became commonplace: people became more skilled at remembering where to look information up but much worse at recalling what that information is.

(How many of your friends’ phone numbers do you know? Maybe none of them. And yet you probably know how to look one up if you need to, say, name someone as a reference in a job application.)

And yet to Thoth’s point, our functional memories are much better as a result of literacy. Writing is much, much more reliable than mnemonics, and more permanent. It’s telling, for instance, that we know about Thamus’s objection to Thoth’s innovation because Plato wrote the story down.

And since the ability to write is pretty reliably available to us, it just works most of the time. Thus the art of memory has faded from widespread relevance.

Which, sadly, means that the things that are hard to write down and organize tend to be forgotten more easily now.

Coming to need our tools

At this point I’d like to adjust the frame of “smarter” and “dumber”. I don’t think one is actually better than the other. I see a real tradeoff between them. My aim is to illuminate the tradeoff so we can think more carefully about where we want to use each type of tool.

Another way to highlight the difference I’m trying to point out is learned dependence.

If you’re a shop clerk, there’s a learning curve involved with using an abacus, but not really with a calculator. The latter just immediately expands your functional arithmetic skills. But it works by outsourcing a certain skill to a black box: you put in the numbers and trust the output. If your black box stops working, your functional skill range suddenly collapses. And possibly to less than you started with, depending on how long and how completely you’ve been relying on the calculator to do all your math for you.

Whereas the effort involved in learning to use an abacus makes you more skilled even if you lose the tool later on. Eventually an abacus will make itself obsolete for its user. One downside is that it takes much longer to learn to use well. And an abacus is much less versatile than a calculator, let alone resources like Wolfram Alpha. Working out something as simple as the cube root of some number is impressively tricky on an abacus but is downright trivial on most scientific calculators.

Part of the key is that an abacus has its user interacting with the structure of arithmetic. Gaining skill means you integrate the shape of numbers into the movements of your fingers. Whereas a calculator lets its user outsource the arithmetic. Any fledgling familiarity with math can atrophy as long as you can prompt the calculator correctly.

But that’s actually maybe fine, so long as you (a) always have a calculator when you need one and (b) don’t have use for the internalized mastery of arithmetic.

Subtle benefits of the harder choice

But sometimes there are hard-to-anticipate benefits to that kind of internalized mastery.

“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”2 If you don’t have well developed numeracy, you’re much more confusable with figures and survey percentages and so on. It’s hard to know what it means for something to cost “$20 billion” versus “$300 million” and what that implies about the US budget. Politicians can fling big numbers and scary statistics around, and innumerate folk will mostly just go with the vibe of what’s being claimed (or agree with their political allies) without really understanding what’s true and what’s ridiculous.

Developing numeracy well enough to be a clear-minded citizen really does require a kind of deep familiarity with numbers and arithmetic. You just can’t develop the right intuitions if you always outsource the intuition-building activities to a calculator. You have to dance with numbers until their rhythms are deep in your bones and nerves.

Another example is in the ancient history of Buddhism. As the story goes, the Pali Canon was passed along orally for about four centuries before being written down. I’ve heard they had a really robust practice: an aspiring monk would recite the canon in front of several others, and they’d be admitted as a full member of the sangha only after demonstrating an ability to recite the canon flawlessly, as judged by others who’d passed (and often administered) similar tests before.

I’d totally expect something like that process to faithfully transmit specific phrases word-for-word for a very long time.

In those first few centuries, I imagine being a monk was a very rich internal experience. There’d be a grueling initial study period where you’d have to listen to spoken sutras, and try to memorize them, and rehearse them like you might do for lines in a play. But by the time you passed your exam, you’d have all the known words and teachings of the Buddha committed to memory. If you put any effort into understanding their meaning along with the words, you’d have an immensely rich library of guidance living inside you at all times. If you ever struggled in your meditation and wondered what to do, a passing thought (or a conversation with a fellow monk) might call to mind exactly the guidance you’re looking for, because it’s already available inside you.

Whereas today, folk can actively and seriously practice Buddhism for decades and still need to reread the Pali Canon. It’s nice that it’s reliably there! And even more searchable today thanks to modern digital tech. But it isn’t reliably deeply a part of every devoted practitioner, precisely because the memory of the Buddha’s words is outsourced. Thamus’s challenge to Thoth very much applies here.

Classical Western education used to encourage something similar. One of the benefits of performing in a Shakespearian play is that Shakespeare’s words become a part of you. It’s easy to look up the quote about someone being “an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”. Today it’s an amusingly fancy way to say someone’s being loud and vapid. But in its original context, the quote is actually something entirely different: the speaker, MacBeth, just learned that his wife is dead. It’s dark, and poignant, and deeply moving. The language is rich and evocative. Taking the time to commit it to heart weaves this moment of story into you, and brings those words and ways of speaking ready to hand and tongue:

She should have died hereafter;

There would have been a time for such a word.

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In a time when dialoguing with AIs causes more and more people to sound like them, the Bard’s grace acts as an elegant antidote. One that cannot be taken through a quick search and citation but must instead be savored and cherished to work its subtle magic.

In short, tools that make you “smarter” (less dependent) tend to enrich you. Instead of expanding your absolute and immediate ability to perform, they expand what you can see and think, over time.

…which is precisely why they tend to be slower to use and offer less scope: they’re enriching you, and it takes time and effort to integrate that enrichment with the rest of your being.

What do we let die?

And sometimes those enriching practices are just obsolete.

A lot of Homer’s stories use a ton of repetition. In The Iliad he starts every single day with the same phrase: “When dawn with her rosy red fingers shone once more….” The redundancy makes the whole poem easier to remember, which was a big help when the story’s survival depended on repeating it word-for-word based on having simply heard it.

Today we solve that memory problem by writing the story down. Rowling has rich detail to the weather of basically every day she mentions in Harry Potter. And it works perfectly well because we don’t have to remember which day has rain or whatever. The page remembers for us.

So it’s totally fine to let our ancient oral memory practices die. We honestly don’t need them anymore. Writing is just better. Our stories are richer for it. We are richer for it.

But there are cases where I have a harder time telling what is or isn’t obsolete.

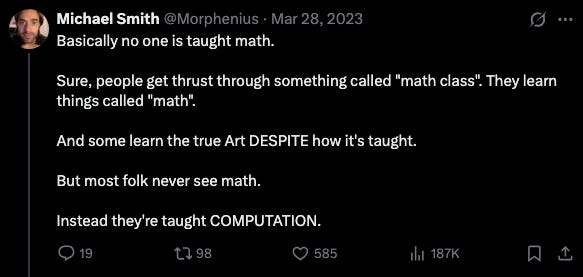

I have a deep love of math. I often want to say that “math” classes don’t teach math at all, and there’s a truly beautiful art that most people never get to see because of it.

So from time to time I’ll look at some detail of math, and meditate on it, to deepen my understanding of something. Simply because this kind of deep comprehension is wonderful and profoundly rewarding.

Recently I was pondering one such detail. It turns out that there’s an intimate relationship between exponential growth and circular rotation. You use the same mathematical tool to track both of them.3 But I didn’t have a good intuition for why that should be true.

Normally I’d spend days or weeks pondering the topic deeply, playing with algebra and geometry, meditating carefully and playfully on the proofs I’m familiar with. It’s a process that strikes me as quite similar to Buddhist insight meditation.4 It takes a while.

…unless you just ask an AI.

It occurred to me that I could turn to Claude and just spell out what I was trying to understand, and ask what the key insight was. So I did, and Claude immediately gave me the answer that made it click for me.5

I feel quite mixed about this result. On the one hand, I’m very excited by the possibility of being able to flesh out my mathematical intuitions much much faster than before. I know where many of my gaps in understanding are, where my technical skill outpaces my insight, and I can just directly ask AI for the key intuitions.

On the other hand, that the slowness before wasn’t pure inefficiency. When I spend days or weeks examining the algebra and meditating on subtle implications, I’m reshaping my mind. I’m noticing approaches that don’t work, and why. I’m using mental muscles involved in juxtaposing lots of intellectual texture, chunking relevant bits together, and groping toward the insight myself.

Skipping all that is a bit like hearing a riddle and then asking an AI to answer it for me. I get the answer much faster, but I don’t get any better at pondering riddles. Maybe the answer grants me some insight that expands my horizons. But it also risks letting some mental strength atrophy. It’s using AI in a way that risks making me dumber more dependent.

But how important is that mental strength? Is it just obsolete now that we have AI?

I find math beautiful, and I want to see more of its beauty. Maybe it’s fine to outsource some of the meditation to AI, the same way it’s usually fine to outsource driving directions to my phone. If I always have AI handy, I can just jump to the math insight, and admire the landscape of mathematical truth much more freely and deeply than before.

And maybe folk working at the frontier of math researchers are in the same position. Maybe the key skill now is asking AI to name the right insights. What if we just don’t need that deep meditative pondering anymore?

But I’m suspicious of that possibility. There’s a glorious experience mathematicians describe when landing on a hard-won insight. The most common term for the sensation is “euphoria”. The ecstasy of discovering mathematical truths is without earthly equal, comparable to the profound pleasure of the first jhana in Buddhist practice. I think you have to grapple with the puzzles yourself to experience that euphoria.

And it’s not just a matter of hedonistic pleasure. The kind of understanding you get after a deep struggle is much more fundamentally a part of you.

So do we want to make this kind of mathematical enrichment be one of the things we cherish and encourage in a post-AI world? One of the things we can never fully outsource?

Or is that meditative skill now obsolete, like Homer’s repetitive storytelling structure? Would we just be better off letting AI do all the struggling at the frontier of math insight, and just handing us key insights so we can appreciate the fruits of labor we no longer need to do?

What do we want to exalt, and what do we want to let die?

I get the sense that we’re just barely starting to notice that this is a question that’s even relevant to ask. Let alone one that might profoundly matter.

How are my tools shaping me?

I’m implicitly answering this question all the time in my daily life. I could, for instance, use Google Maps to look at a suggested driving route and then just try to drive without navigation. And maybe pull over and check my phone if I get disoriented. But most of the time I just use the real-time driving directions. I basically always have my phone, and navigation basically always works, so it’s not all that important for me to retain my “memorize driving direction” skills.

On the other hand, most of the time I use a calculator to check my mental math rather than to do it for me. I care about keeping my numeracy sharp, but also about getting the right answer. So if I’m unsure I can check with Siri once I’ve given it a go myself.

(Examples like these add some nuance to the tool type distinction I started out with. It’s not really that tools themselves make me “dumber” or “smarter”. It’s that they encourage being used a certain way, and how I use tools can make me more or less dependent on them over time.)

The same thinking shows up with, say, grocery lists. I used to use mnemonics for those. And doing so is fun! It’s just less reliable than writing the grocery items on a piece of paper (or in an app) and then checking it while at the store. When I do the latter, I’m letting my memory skills atrophy. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, like us losing the habit of Homer-style repetition in our stories wasn’t a bad thing. But it does happen. And if I care about my mnemonic skills, I might want to adjust how I use lists. E.g., I could make the written list, but check it only after trying to shop using some mnemonic method to remember all the items. Then the list becomes a way to train my memory instead of replacing it.

I’ve started using LLMs for a lot of search queries I used to use Google for. I can tell that some of my “dig through the internet to find and verify information” skills are getting less practice now. But in most cases I’m okay with that. It used to take me a while to find solutions to even try for things like “My whiteboard won’t wipe clean” and “I want my soup to thicken.” I’m quite happy to just get answers basically right away, even if I need to check them a bit.

The place where it gets more suss (for me) is when I outsource remembering an explanation to the AI (or to Google-like searches for that matter). Once I really understand how (say) cast iron seasoning works, I can easily remember how to take care of it.

But if I read an explanation of seasoning and treat it as entertainment, and just assume I can look it up later and therefore isn’t something I need to really take in, I feel like I’m depriving myself of an inner richness. I’d be letting my deep sense of how reality works atrophy. I don’t like that. Understanding is one of the things I personally never want outsource to AI.

For a similar reason, at this point I don’t let AI do any of my writing. I’m enriched by the act of articulating, and working my pieces, and massaging my ideas and words. I’m sure I would output some of my ideas more quickly if I used LLMs. But right now I don’t care. It feels like using a calculator to get through my mental math practice. My aim isn’t to hop to the end. It’s to enrich myself with the process.

But I’m happy to let AI create some images for me. I’m not the image-creating artist type, and I don’t currently have much of a drive to become one. In the pre-AI era, that’d mean I’d need to just put in time getting good at drawing or picture-taking or whatever in order to visually express what I mean. And that would be enriching in some ways! But I’d rather pour my self-enrichment time elsewhere right now and for the foreseeable future. So the freedom to skip that particular training montage is very welcome.

I see myself making choices like this all the time. When I remember my schedule by looking at my calendar rather than trying to call it to mind, or when I take the escalator instead of the stairs, or at what point I ask for help when having trouble with some piece of software.

There’s often a tradeoff between

(a) getting the current problem solved versus

(b) improving my overall ability to solve problems like the one at hand.

I like at least noticing when I’m making such a tradeoff. And giving myself the chance to decide if I want to change the direction I’m leaning in some way.

In Phaedrus Thoth is called “Theuth”. I’m choosing to use the more recognizable form of his name here though.

No one’s quite sure where this phrase originates, but in 1907 Mark Twain attributed it to Benjamin Disraeli, a 19th century British political figure.

For those with some math background, or just simple curiosity: I’m talking about the exponential function with base e. It turns out, for instance, that you can derive basically all trigonometric identities from the fact that imaginary numbers map onto the unit circle under exponentiation:

Specifically samatha-vipassanā, which is to say, a fusion of concentration and clear seeing. A key difference being that in Buddhist vipassanā, you’re trying to see through the nature of every sensation (specifically to the three characteristics). Whereas in math, you’re trying to see the necessity within the sensations.

Maybe we should try spelling out everything in millions, because "twenty thousand million" sounds worlds bigger than "three hundred million" in a way that "twenty billion" doesn't.

Brillant take on Thamus's objection to writing, framing it not as wrong but as a legit tradeoff we've been making unconsciously for centuries. I once tried memorizing math proofs the old-fashioned way and the struggle actualy did wire the intuition deeper than just looking up solutions ever could. The part about AI turning math meditation into instant answers hits close tho because I dunno if we're ready to decide which mental muscles are actually obsolete vs just inconvenient right now.