Bad Teaching

All life wants to learn. Just let it.

I want to rant about bad teaching.

I keep seeing folk complaining about students “cheating” with AI. Submitting essays spat out by ChatGPT or whatever.

I agree that it’s distasteful. It’s sad that this is the situation we’ve wrought.

But the problem isn’t the students. And it’s not the tool.

The problem is that we’re used to making students do something they don’t want to do, and now they have a way around our coercion.

I got a Ph.D. in math education. It’s silly that that’s relevant, but here we are. The point is, I’ve spent a lot of time staring at how people learn and teach math, and the psychology of math, and I have Opinions™. Some of which apply to teaching in general.

I remember when WolframAlpha first showed up. I celebrated. I thought it just might force an end to the coercive paradigm for teaching math. It’s a super-calculator that could make homework trivial.

But that isn’t what happened. Instead classes kept and reinforced their shape that made the tool hard to use in quizzes and exams. (Gotta ban those smartphones during tests! Just like the calculators, right?) So students could still be forced to learn how to (say) factor quadratics on their own.

Never mind that WolframAlpha would be available to them if they ever actually had a quadratic they needed factored.

I find this entire approach to education sickening. It’s absurd. I understand how we got here, and I don’t think most teachers are to blame for it. But the whole thing is really dumb.

And now I think we’re being confronted with the need to do better. Again. But louder.

But I’m getting a little ahead of myself. Let me lay out the problem as I see it.

Coercive math

I used to teach math classes in universities. Mostly topics like precalculus and business statistics. The sort of courses that no one would take in college if they weren’t required for a degree.

So, unsurprisingly, students would do whatever they could to pass. Sometimes that involved studying. But quite often that amounted to arguing with me about whether their exam answers should “count” and be given more points.

(It’s also impressive how many grandmothers got sick right before midterms. Utterly stunning. And nearly always grandmothers specifically. Pure coincidence I’m sure.)

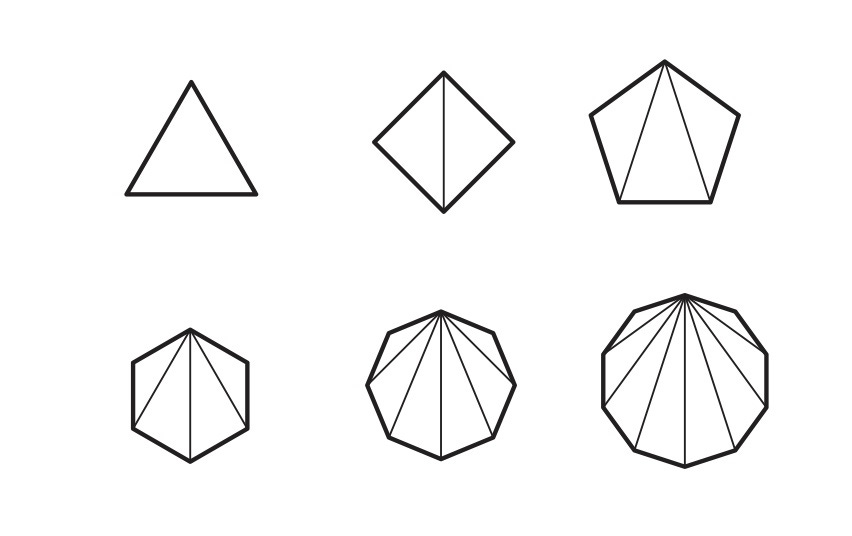

I remember at one point I was teaching a class on geometry for people who were hoping to become middle school teachers. We were covering the kind of math they’d need to master in order to teach children well. I’d given them a formula for finding the sum of the internal angles of any polygon based on a particular way of cutting it into triangles:

Since we know the sum of the internal angle of a triangle (180 degrees), you just have to count the number of triangles. It turns out that’s always going to be two less than the number of sides of the polygon. So you get a formula that looks like this:

(n–2)*180

Separately I also showed them some proofs that the sum of the internal angles of a triangle is 180 degrees. I won’t torment you with one of those. Just know they exist, and the students saw them.

So on their exam, I asked them to explain their reasoning for why the sum of the internal angles of a triangle should be 180 degrees. And most of them responded with:

(3–2)*180 = 1*180 = 180

Because, you know, a triangle has three sides. So you plug n = 3 into the formula.

It’s possible you don’t see the problem here. Lots of people don’t. But I promise you, as a mathematician turned math teacher turned philosopher, this is forehead-slapping. It’s really not an explanation of anything. It’s literally saying that if you cut a triangle into triangles, you get one triangle, and therefore the sum of the internal angles of your triangle should be… the sum of the internal angles of one triangle. That’s literally the reasoning that just happened. The “180” is there purely because that’s the formula I gave them. If I’d put “360” there then that’s what they’d have written instead.

When I handed their graded exams back to them, there was a small revolt. The students thought the question was unfair. I mean, so many of them got it wrong, so clearly it wasn’t fair!

We spent over twenty minutes discussing why the common answer they gave didn’t make any sense. Eventually when they could see that I wasn’t going to budge on the logic, one of them objected:

“But you didn’t say we couldn’t use that formula!”

To which many of the other students adamantly nodded.

“Yeah! You didn’t! So your grading isn’t fair!”

I again want to emphasize that perhaps you, my dear reader, have been traumatized by bad math teaching. Perhaps you do not see the problem with what the students were doing here. If so, I do not blame you.

But I want to assure you that it is quite maddening. Truth does not care what is “fair”. Their logic would not make sense even if I had caved to their demand for more points.

At the time I was bewildered and frustrated with the students. I now think this was an error on my part. I think I was confused. I was in fact contributing to the very system that I now see as utterly insane in this regard.

The problem was that the students were solving a different problem. They weren’t trying to understand something about polygons. They were trying to get through a required course.

They were — correctly! — solving a social problem. The one they actually cared about. I was basically the authority figure standing in their way. (Hence “unfair”, like we were in some kind of competition.) And I was trying to force them to learn something they had no reason to care about other than due to my threat to not pass them if they didn’t learn it.

The absurdity here is that the education system has made teaching adversarial to students’ interests. Students have to get through exams in order to get what they want. And they have to learn some seemingly arbitrary things in order to get through exams. So learning pointless nonsense is the obstacle course some authority requires them to navigate, on pain of withholding what the students actually care about.

It strikes me as extremely telling that children — children, for God’s sake, who are known for their voracious love of learning — so very often dislike school, which is nominally about learning.

This should be an extremely loud warning sign that we aren’t doing what we think we’re doing.

“Cheating” at writing

Let me switch back to the topic of using AI to write essays.

With a great deal of empathy for their plight, I’ve been reading a lot of English teachers complaining about their students submitting slop. A lot of the students’ work is pointless tripe. Some of it is soulless AI blather. Nearly none of it is students having poured their souls into articulating something dear to them and refining their expression.

There’s fear that AI and social media and whatever are degrading students’ ability to think and argue. Undergraduates can’t do literary analysis anymore. Many of them quite literally cannot read books from the Western canon: they just don’t have the attention span for it.

That really is a sad state of affairs for our civilization. It’s a problem for us to address collectively. Or at least it’s an effect we’re going to feel the impact of one way or another. It might result in collective cultural amnesia and even more social fragmentation than we have now.

But here’s the thing: I don’t think the students are doing anything wrong. I don’t think they’re “cheating” by having AI write for them. They’re solving the problem they’ve been handed. They’re told they have to navigate this class to get the degree or diploma they need, and that they have to produce a bunch of written words to navigate this class… so of course once they have an essay machine, they’ll use the machine to solve their problem!

Just like with math classes, the problem is the adversarial setup. You can’t coerce people into wanting to learn. You can at best trap them into having no available choice than to learn something. You can threaten them into pretending to learn.

But frankly at this point that’s just a shitty thing to do to a person. It maybe made sense mid 20th century when conformity helped a functional culture support nearly everyone. But today? Where our systems aren’t coherent or trusted enough for students to see the point of reshaping their lives to fit into them? At this juncture there’s no reason to carve people into cogs of a broken machine. That’s bad for them and frankly might be bad for the machine too.

Here’s how I think you fix an English class — bearing in mind that I’ve never taught English. I’m experienced in math education and have many strong opinions that sure seem to apply. But I might meaningfully not know what I’m talking about when it comes to teaching literature and writing. And yet I’m going to assert opinions about it anyway:

I think you fix post-LLM English classes by appealing to the students.

Supposedly they’re learning something of value to them from writing. Right? Things like how to organize their thinking, and how to express themselves better, and how to persuade others. Joining the centuries-long deep discussion that built today’s world. Enriching their souls.

If these things are relevant to what the students care about, and if you can demonstrate that you can offer these things to them, and you can show them how learning to write well is key to this process, then you won’t have to battle their urges to “cheat”. They’ll get that it’s not about producing an essay to beat the system. It’s about practicing writing well so that they can live better lives.

It’s like that old quote:

"If you want to build a ship, don't drum up people to collect wood and don't assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea."

If you put in the work to lure students to feel why they already care about learning the art of skillful writing, then you won’t be able to stop them from learning. You’ll just be a facilitator. You’re there as a masterful guide of the domain that they’re so keen to explore.

And then you can warn them about AI. You can show them the result of applying AI to thinking, and persuasion, and how it actually weakens them if used wrong. Not that it’s a bad tool, but that it’s a bad substitute for learning to express themselves. And how using it that way can harm things that the students care about if they’re not careful.

If they get all that, then your class isn’t adversarial anymore. It’s cooperative.

Some teachers really do understand this point. The best ones.

It’s weirdly rare though. We’ve all been modeled really, really bad teaching.

Punching nothing

You might think the problem I’m pointing out here is coercion. That we’ve set up an adversarial incentive between students and the system that’s trying to make them learn.

And I think that’s basically right. But I think there’s a deeper error causing this one: the feedback loop is through a social authority instead of through the topic the students have drive to learn.

Let me give a very different example: martial arts. This is a case where, for the most part, students aren’t motivated to “cheat”. They’re not trying to, say, get a job that requires them to have a black belt. So they’re not going to argue with the teacher about whether their performance on their black belt test deserves to get more points. That’s just silly.

But it’s absurdly common for the teaching to still be based on social authority.

A few months ago I watched a Shorinji Kempo class. At one point they were practicing a specific kind of punch. Over and over again striking in the air as the instructor counted in Japanese.

This is something like shadowboxing. But in shadowboxing, you’re refining something you hopefully learned while hitting a punching bag. You noticed how you tend to forget to pivot your foot at the right moment, or how you need to lift your elbow a bit more, or whatever. So you rehearse that movement to correct errors you recognized when the bag (or a sparring partner) was giving you real-world feedback.

But that’s not typically what’s going on in traditional Japanese martial arts classes in my experience. It’s more like, students are told to mimic roughly what learning looks like. So you practice punching in the air because that’s what the teacher tells you to do. And you obey the teacher. ‘Cause that’s what you do.

At one point the instructor paused the students and said something like this:

When you’re doing this strike, make sure your knee is pointing in the same direction as your fist. Don’t let it waver to one side or the other. Get them both aligned in the same direction.

This style of correction is madness.

Again, as with the math example up above, there’s a good chance that you don’t see the problem. Totally understandable. I think missing it is an artifact of the ubiquity of terrible teaching. It’s so normalized that it’s often hard to notice.

The problem here is that the feedback loop is totally wrong. The students will probably adjust their postures, but it’s in order to conform to an authority. They don’t know why they should get their knees and fists aligned. Even if they already knew about this alignment thing (because they’d been told), they don’t know why their bodies didn’t adhere to the instruction before. Bodies are quite intelligent and will become efficient at what they repeatedly do. So if there’s a natural tendency to let the knee drift in this strike… why? And what exactly is the problem with misalignment such that the natural tendency is worth correcting?

But instead of inviting students to ask questions like these and explore, the instructor just told them which authoritarian instruction to mentally impose on their movement patterns.

People these days sometimes talk about “decolonizing the mind”. Here’s an example of colonizing the body. Literally bypassing your own visceral knowing so that some authority figure can directly write their will onto your nervous system.

Here’s what I would do as the instructor (noting that while I’m very experienced in martial arts as both a student and a teacher, I haven’t trained in Shorinji Kempo, so maybe I’m missing something about that art in particular):

I’m guessing that the knee/fist alignment thing is about stability and strength. So I’d have the students keep shadowboxing, and while they do that I’d go up to each one and catch their fist and push in a way that’d make them stumble. I’d then have them mess around with different body positions until they stop stumbling when I push. I would avoid telling them what to adjust! I’d have them generate the exploration for themselves. At most, if constraints of class time required me to move on before their natural learning process would complete, I might suggest that they try moving their knee around as well to see what happens.

This approach plugs students into the right feedback loops. Instead of attuning to an authority figure, they’re feeling the physical reasons for the adjustment. When they’re shadowboxing later on, they’ll feel the weakness, and that feeling will remind them to adjust. If some other teacher later comes along and tells them that they should deviate their knees, they’d have reason to object and to ask for clarity. Their knowing would be rooted in a direct personal relationship with the physical skill, not in conformity to some kind of socially proclaimed ideal.

There might be other, more clever ways of getting this result. I might pair students off and have them do games involving the strike, for instance. But the point is that as the teacher, my job isn’t to tell students what outcome to reach. My job is to help them get the right feedback so that they can tell what they want to learn and whether they’re learning it — ideally in a way that eventually makes me obsolete!

The core of bad teaching that I’m pointing at here is, giving feedback loops through authority instead of through direct contact with the truth. Telling the students what outcomes to produce instead of where to look to develop a skill they care about.

Learning well anyway

This kind of bad teaching is everywhere. It seems to be the thing most folk default to. It’s how most instructors teach, and it’s what most students are trained to seek out when they want to or have to learn.

I honestly don’t know why it’s like this. Bad teaching is a tendency I have to resist in myself too. I have guesses about its cause. Many people do. And maybe figuring that out would help us fix it.

But the main pragmatic point is, it’s everywhere. Good teaching is surprisingly rare once you know what to look for.

Which means that if you want to learn skillfully, you need to account for two things:

The best sources of information are often poor sources of feedback. You have to check the feedback loops yourself. Often you’ll need to fix them, or find or create new ones on your own.

You need to keep an eye out for your own tendency to conform to some social ideal that masquerades as “learning”. Notice when you’re inclined to use an expert’s opinion to check what you’re doing instead of to guide your attention. Beware being told when you’re doing well!

For instance, if you want to learn a martial art, it’s helpful to notice when you’re being told how to contort your body without being guided to feel why. Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu classes tend not to make this error because the feedback loops are so clear: you roll with someone and find out why a technique has to be done a certain way. But most martial arts classes teach traditionally, which tends to mean poorly. So you have to figure out ways of getting good feedback loops yourself.

After I watched that Shorinji Kempo class, I went to a punching bag and experimented with moving my knee around as I hit the bag. That’s how I came to my guess that the knee thing is about stability and power. Striking the bag with my knee deviated made it harder to avoid stumbling. It also put a tiny bit of torque on my knee in a way that I think could eventually become unhealthy. Now my knee and fist align without my having to think about it because any other movement type with that strike feels wrong.

That’s an example of what I mean by seeking your own feedback loops. Reality becomes your teacher.

Another example is in math. Math Academy does an absolutely amazing job at the authority-based style of teaching. But it’s still glitchy in the way I’m talking about. It’s excellent bad teaching. They tell you what you’re going to learn, and how to solve problems, often without guiding you to even understand why those computation techniques work. But it’s still a great resource! Its lessons are still correct. That material is powerful for mastering domains of computation, which can be a wonderful foundation for a lot of different STEM disciplines. It just means that if you want to actually understand math instead of having pure computation and obedience authoritatively pounded into your skull, you have to seek your own feedback loops.

Math in particular is quirky in that you can get good feedback loops basically by thinking. As a kid I used to solve algebra problems very slowly so that I could think through why each move made sense. Sure, I can quickly isolate x by dividing both sides by 3 or whatever… but I needed to stare at what it meant in order to understand it. Like to solve 3x = 15 I’d think:

“Okay, so if triple this unknown quantity is the same as fifteen, then I can break both the triple and the fifteen into thirds. That gives me six pieces that are all the same size. Three of them literally are each the unknown quantity. The fifteen breaks into three pieces of size five. So the unknown quantity is five.”

That’s a lot of extra steps. I could have gotten the answer faster by just dividing both sides by 3. But my goal wasn’t to just get to the end. My aim wasn’t to have done a bunch of math problems. My desire in my case was to deeply master a type of reasoning. So if some step felt like magic to me, I would spend time staring at it and tracing the reasoning until it went from “I guess it works” to “Oh, it absolutely must work this way! I can tell for myself!”

Math Academy tends to punish you for going slowly like this. Whatever. If you use it, but you want to understand mathematics instead of just computation, keep the brokenness of their feedback loops in mind. You’re not there to please Math Academy. Keep your eye on what you care about.

I dislike Duolingo’s achievements and streaks for a similar reason. They motivate the wrong thing. If you need gimmicks to learn a language, then why are you learning the language? Why not relate the reason you’re learning the language to how you learn? The most common reason I’m aware of is that most teaching is bad this way, and building good feedback loops is often hard. It’s easier to just use the easily available bad feedback loops. But you’ll tend to learn the wrong thing if you do that. (How many Americans have spent years studying a foreign language and still can’t speak it?)

Keep coming relentlessly back to what you’re trying to learn, and why. Seek out ways of practicing and mastering what matters to you instead of getting some expert to tell you that you’re doing a good job.

It can be weirdly hard to guide your own learning this way. But on net it’s both much faster and vastly more rewarding.

Good teaching

And if you’re a teacher, formally or informally, or if you design systems meant to teach people something, I beg of you:

Please, for the love of everything good in this world, please pay attention to the feedback loops you’re giving learners.

Your job is to put yourself out of a job.

Your expertise means you can see the actual truth and the feedback loops that plug you into it. And maybe you can notice which forms of feedback students are likely to overlook or take a long time to discover on their own.

Once they’re plugged into the truth directly, they don’t need you anymore. Reality becomes their teacher.

That is extremely good.

If you’re very good at what you do, you can turn students into colleagues. You might always be more skilled than they are, and you might always have more to teach them. It turns out that reality has a surprising amount of detail. There’s no end to the relevant feedback available. So if you have a head start, you might always have more you can show those who are less experienced than you are.

But if you do your job well, they will discover things you’ve missed. They’ll become masters of areas that might even be relevant to you and that you’ve always had trouble with.

This is part of the beauty of us all being in relationship with each other. We are different instances of life. Different souls. We see the everything differently from one another. We can come together and see the world more deeply than any one of us could have on our own.

You want that opportunity. You want to let your students grow into collaborators who can help enrich us all, including you.

Or rather, I don’t mean to presume what you in particular truly want. Maybe you mostly want prestige! I don’t know.

But I think there’s something really beautiful possible here, if it were more widespread.

In particular, please be especially careful with how you use your authority. If you tell students that they’re doing a good job, or that they missed something and need to adjust it, what are you training them to do with their attention? Where will they habitually look? Most of the time that type of interaction makes students more dependent on the teacher!

Again, your job is to make yourself obsolete to each student. What questions can you ask them that will guide their attention to the right feedback loops? Good teaching is mostly not about clear explanations. It’s about inviting your fellow human beings to notice for themselves that reality is constantly whispering precious secrets to them.

And please, please let students be the authority on what’s relevant for their own learning. Stop trying to make them learn things that they don’t see the point of. If it’s valuable to them, then show them the value. Let them feel it. Give them a longing for the endless immensity of the sea. That’s much harder to do than requiring things of them from a position of authority, but forcing people to learn things they don’t care about is quite frankly cruel. And we’re thankfully losing the ability to do it anyway.

And if you don’t know how to convey the value of what you have to offer, but you’re quite sure it is worthwhile to them, then earn their trust. Ask them if they’re willing to test your guess that they want what you have to give. Give it well. And then at the end, sincerely and humbly check with them: “Was I right? Was this worth your while?”

If you’re well-attuned to what matters to them, you will tend to be right, and they’ll see that. Then they’ll correctly tend to trust your suggestions about what to explore.

Just beware making them dependent on you. Ask for blind trust sparingly. It’s a path that readily leads to bad teaching. Keep turning them back to the feedback loops that don’t involve you.

Again, your job is to free each student of the need for your guidance.

I think there’s a much brighter possibility in humanity’s future than attempted forced obedience and low attention spans and AI slop.

Let’s focus on the learning that’s actually relevant, that’s soul-enriching, that helps us build a good society, that lets us talk more deeply with one another, that lets us recall and contend with the deep questions that brought us to today’s conundrums.

Let’s teach and learn beautifully.

wow, I love this! I've had the pleasure of having had some really good teachers in the last year and it makes such a big difference! that's when you can start coming up with your own exercises specific to your needs because you have understood the principle of how learning the skill in question might work...

AIs too! "The models—they just want to learn." — Dario, quoting Ilya:

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/CM_DP7pkJQk